Teaching is "a dynamic endeavor . . . [that] must be carefully planned, continuously examined, and relate directly to the subject taught" (Boyer, 1990, pp. 23-24). Dewey advocated learning that was active; student centered, and involved shared inquiry.

What is a Faculty Learning Community (FLC)?

The concept of the learning community was born in the 1920s and 1930s with the work of Alexander Meiklejohn and John Dewey. Both were concerned about increasing specialization and fragmentation in higher education1. It wasn't until the mid-1990s that interest in faculty learning communities began to grow.

A faculty learning community (FLC) was defined at Miami University as a cross-disciplinary faculty and staff group of 6 to 15 members (8 to 12 members is the recommended size) who engage in an active, collaborative, year-long program with a curriculum that enhances teaching and learning, and includes frequent seminars and activities that provide learning, development, the scholarship of teaching, and community building2. FLC is a structured framework that continuously assesses faculty needs in order to enhance faculty professional development.

Types of FLC:

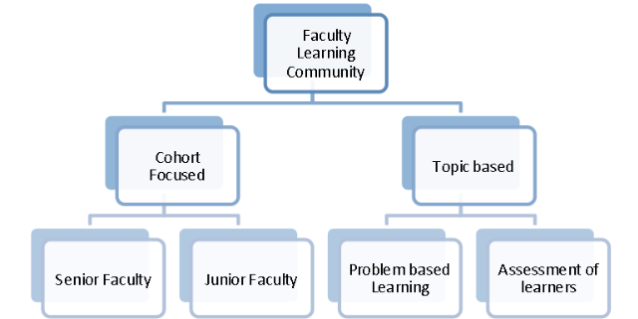

FLCs are described as either topic or cohort based.

Cohort-focused FLCs:

These communities target the developmental needs of a specific group of faculty in teaching and learning, such as the needs of junior faculty to attain scholarship, or enhancing leadership among senior faculty. Two examples of cohort-focused communities at Miami are the Teaching Scholars Program, which provides peer consultation for junior faculty, and the Senior Faculty Program for Teaching Excellence, which is designed to provide support for midcareer and senior professors.

Topic-based FLCs:

These communities identify certain topics or learning issues that should be covered by faculty in the institution. Examples of topics that enhance faculty development are assessment of undergraduate or postgraduate learners, incorporating different instructional strategies, and evidence-based teaching methods.

Enhancing the Scholarship of Teaching

Scholarship of teaching is not synonymous with excellent teaching. It requires a kind of "going meta," in which faculty frame and systematically investigate questions related to student learning.3 Scholars of teaching are excellent teachers, but they differ from excellent or expert teachers in that they share their knowledge and advance the knowledge of teaching and learning in the discipline in a way that can be peer-reviewed.4

FLCs provide an excellent structure to help faculty members develop scholarly teaching and create the scholarship of teaching and learning, in part due to the deep learning that can take place in an FLC.5 Examples of scholarly activities that can be incorporated in FLC are course design, course redesign, teaching/course portfolios, presentations, and publications. Creating a safe, supportive environment or community of educators, mentoring new participants, providing structured forums for conducting presentations and disseminating projects will result in an effective development of scholarship of teaching. Evidence suggests that the development of and participation in FLCs may result in significant improvements across disciplines and faculty lines.6 Moreover, FLCs increase faculty interest in teaching and learning and provide safety and support for faculty to investigate, attempt, assess, and adopt new methods.7

Transforming institutions of higher education into learning organizations

Organizational learning is described in several ways. It is said to be the cumulative product of the learning of small groups or teams;8 and the collective learning that occurs in an organization that has the capacity to impact an organization's performance.9, 10 It is also described as a process of increasing organizational effectiveness and efficiency through shared knowledge and understanding.11 FLCs have the potential to transform institutions into learning organizations by converting individual knowledge into explicit knowledge; involving faculty in periodic symposia and retreats; disseminating the culture of innovation; and encouraging project presentations in national and international conferences. Creating a faculty learning community program is one approach that engages the community to improve student and faculty learning and can transform our institutions of higher education into learning organizations.12

Improving student learning

Adult learners construct their own knowledge; combining their previous experiences with new knowledge and creating their own new understanding.13This is the base of Constructivism theory that promotes the development of lifelong self-directed learners. FLCs shape the way learners are taught through creating new teaching and learning experiences. Designing and redesigning curricula, incorporating various instructional strategies and use of new technology to enhance learning, have contributed tremendously in improving the courses that enhance students' learning. Moreover, FLCs exert greater emphasis on student engagement and collaborative learning. Kuh (2001) and Pascarella (2001) posited that a quality undergraduate education was one that engaged students in proven good educational practices (e.g. focus and quality of undergraduate teaching, interactions with faculty and peers and involvement in coursework) and that added value to student learning.14 First-year students and seniors reported greater gains in personal social development, general education knowledge, and practical competencies on campuses where faculty members engaged them using active and collaborative learning exercises.14

Peer to Peer consultation

Faculty learning communities can facilitate peer consultation and broaden the scope of its impact on individuals and institutions.1 They offer opportunities for faculty to seek advice from each other regarding teaching and learning concerns and furthermore enable them to identify their own needs through enrollment in discussions in the regular meetings, periodic seminars, retreats and conferences.

Conclusion

FLCs enhance the learning and teaching culture in institutions. Administrators have a vital role in fostering the creation, development, and sustainability of FLCs. With thoughtful planning and faculty and administrative support through faculty rewarding, developing and facilitating policies, and removal of obstacles, the culture of FLCs can be created in any institution.

The growth of any craft depends on shared practice and honest dialogue among the people who do it. We grow by trial and error, to be sure - but our willingness to try, and fail, as individuals is severely limited when we are not supported by a community that encourages such risks.

Palmer, 1998, p. 144.

References

- Cox, Milton D. "Peer consultation and faculty learning communities." New Directions for Teaching and Learning 1999.79 (1999): 39-49.

- Cox, Milton D. " Introduction to faculty learning communities." New directions for teaching and learning 2004.97 (2004): 5-23.

- Hutchings, Pat, and Lee S. Shulman. "The scholarship of teaching: New elaborations, new developments." Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 31.5 (1999): 10-15.

- Kreber, C. (2002). Teaching excellence, teaching expertise, and the scholarship of teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 27(1), 5-23 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1020464222360

- Richlin, L; Cox, MD. Developing scholarly teaching and the scholarship of teaching and learning through faculty learning communities. New Directions for Teaching & Learning. 2004, 97, 127-135, 2004. ISSN: 02710633

- Little, Jennifer J., et al. "Interdisciplinary collaboration: A faculty learning community creates a comprehensive LibGuide." Reference Services Review 38.3 (2010): 431-444.

- Cox, Milton D. "Achieving teaching and learning excellence through faculty learning communities." Essays on Teaching Excellence: Toward the Best in the Academy 14.4 (2002).

- Levinthal, D.A.; March J.G. The myopia of learning. Strat. Manag. J. 1993,14, 95-112.

- Goh, S.C.; Chan, C.; Kuziemsky, C. Teamwork, organizational learning, patient safety and job outcomes. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2013, 26, 420-432.

- Bapuji, H.; Crossan M. From questions to answers: Reviewing organizational learning research. Manag. Learn. 2004, 35, 397-417.

- Conway, J.B.; Weingart S.N. Organizational Change in the Face of Highly Public Errors. I. The Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Experience; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA. Available online: http://www.webmm.ahrq.gov/ perspective.aspx?perspectiveID=3 (accessed on 7 January 2014)

- Cox, Milton D. "Faculty learning communities: Change agents for transforming institutions into learning organizations." To improve the academy 19.69-93 (2001).

- Jean Piaget, 1967

- Umbach, Paul D., and Matthew R. Wawrzynski. "Faculty do matter: The role of college faculty in student learning and engagement." Research in Higher Education 46.2 (2005): 153-184.

- Aragon, Steven R. "Creating social presence in online environments." New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education (San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2003) (2010): 57-68.

Written for September 2015 by

Shireen Suliman, MD

Clinical Fellow, Internal Medicine Department

Hamad General Hospital

Hamad Medical Corporation

MEHP Fellow, John's Hopkins