Self-Direction in adult learning has been a topic of increasing interest and investigation by scholars and practitioners of adult education since the mid 1900’s. Different educators have represented it with a variety of terms, such as self-education, andragogy, self-directed learning, independent study, autonomous learning, self-planned learning, adults’ learning projects, independent study, lifelong learning and auto-didacticism. But each of these terms emphasizes the self-imposed responsibility of the individual learner in the learning process (Guglielmino et al, 2005). Probably the best definition of self-directed learning is that provided by M. Knowles (1975):

“In its broadest meaning, SDL describes a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes”

Knowles is the main educator behind the theory of andragogy or adult learning. As such, he proposed that learners become increasingly self-directed as they mature. SDL can be considered as learning by oneself (auto-formation), as opposed to learning through the actions of others (hetero-formation) (Carre, 2011).

Merriam, Caffarella and Baumgartner (2007) have described 3 main goals for SDL:

- To enhance the ability of learners to be self-determined in their studies.

- To foster transformational learning.

- To promote emancipatory learning and social action as an integral part of SDL.

Goal one is clearly anchored in humanism, which poses that learning preferably, should be self-initiated, with a sense of discovery coming from within (Rogers, 1983). Those grounded in a humanistic philosophy posit that SDL should have as its goal the development of the learner’s capacity to be self-directed (Merriam, 2001; as cited in Hiemstra, 2013). I believe, in agreement with Knowles (Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 1998; Merriam, Caffarella, & Baumgartner, 2007), that ideally, as learners mature, they move from a self-dependent personality towards one of self-direction and autonomy. This constitutes both a process and a desired outcome, and our role as educators is to facilitate this process. I also think, that whenever possible, we should foster in our students motivations for learning that are internal rather than external. As mentioned by Knowles & Associates (1984), internal motivations are usually more potent and effective; and more consistent with a truly independent, autonomous and self-motivated desire to learn and to change.

Goal two is anchored in the work of Brookfield (1986) and Mezirow (1985), who considered that the critical reflection process, as an intrinsic and critical component of SDL, leads to transformational learning. Furthermore, critical reflection and transformational learning support the third goal of promoting emancipatory learning and social action (Merriam, Caffarella, & Baumgartner, 2007). The latter is also grounded in the work of the prominent educator P. Freire, who considers that through critical reflection and SDL students can truly emancipate themselves and exert positive social actions. Self-direction and self-determination can only be achieved when we favor problem-posing education, which solves the student-teacher contradiction by recognizing that effective knowledge is not deposited from one (the teacher) to another (the student), but is instead formulated through critical thinking and dialogue between the two (Freire, 1970, 2000).

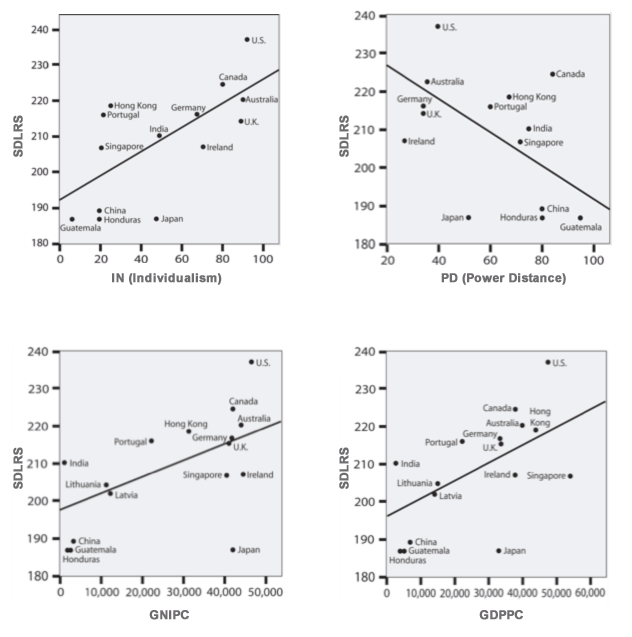

It is interesting to consider the study completed by L. Guglielmino (Guglielmino, & Guglielmino, 2011), who studied SDL levels in 17 countries and showed a strong positive correlation between SDL and economic development, productivity and individualism, and also a robust negative correlation between SDL and power distance. Please see figures and definitions below:

- GNIPC: Gross National Income Per Capita, GDPPC: Gross Domestic Product Per Capita.

- Power Distance (PD): Extent to which less powerful members of societies accept unequal power distribution. In cultures with high PD, followers as much as leaders endorse society’s inequalities.

- Individualism (IN): IN and its opposite, collectivism, are the degree to which individuals are integrated into groups. In individualistic societies ties between people are loose (you are expected to look after yourself). In collectivistic societies people are integrated into cohesive groups, often extended families that protect them in return for loyalty

Another study by Frambach and collaborators looking at three different medical schools worldwide also identified that SDL abilities relate to prior educational and cultural backgrounds (Frambach et al, 2012). In this investigation, factors that posed challenges to the development of SDL included uncertainty about the independence required for autonomous learning, a dependence on hierarchical sources, a focus on tradition that impeded the uptake of a new approach to learning, a pressure to achieve rather than an intrinsic motivation to learn, and a prior traditional teacher-centered secondary school education. Therefore, it seems that the aspiration for learning, and the outcomes of that learning, are influenced by culture, so the learning responsibility locus may be located in the individual or in the collective (Poole).

In other words, it might be more difficult to promote SDL as a pathway to transformational and emancipatory learning in traditional collectivistic societies that accept unequal power distribution, or that demonstrate low income and low productivity. Interestingly, Brookfield (1993) has proposed that, “any authentic exercise of self-directness requires that certain political conditions be in place”. One consistent element in the majority of definitions of SDL is the importance of the learner's exercising control over all educational decisions: what should be the goals of a learning effort, what resources should be used, what methods will work best for the learner, and by what criteria the success of any learning effort should be judged are all decisions that are said to rest in the learner's hands. This emphasis on control on who decides what is right and good, and how these things should be pursued, is also central to the notion of emancipatory adult education. Self-direction therefore calls to mind some significant political associations. It denotes a democratic pledge to shifting to learners as much control as possible for designing, conducting, and evaluating their learning. If we place control of learning at the center of the definition of SDL, we immediately raise questions about how control can be effectively exercised in a culture or society which is itself highly controlling. Can learners very truly self-directed in a setting that excludes certain ideas as subversive? A fully developed adult form of SDL can only grow when we critically examine and reflect about our definitions of what we think it is important for us to learn, and the extent to which these definitions might be serving others’ hegemonic interests (Brookfield, 1993).

However, it is also valid that the “self” that is in control of learning is unavoidably culturally formed and biased. The “self” can never be a “pure and immaculate self”, free from cultural or political influences. We cannot deny that learning, including of course SDL, always happens in cultural contexts (Flannery, 1993). Even the most critically reflective educators, with the highest levels of insight, cannot escape their own life stories and determinants. Nevertheless, still through our personal efforts (reflection and auto-examination), and help from others, we can become aware of how what we view as useful and positive educational decisions, in reality may sometimes represent hegemonic and culturally biased assumptions. Ultimately, we cannot become self-directed learners, or promote SDL, if we don’t know ourselves, including our personal and cultural preconceptions. And the only way to “know” ourselves, and gain insight about our motivations, is through critical reflection, either through auto-analysis, or reflection with others.

Candy (1991), however, also notes that this commitment to SDL sometimes leads to forms of false democracy in which educators feel they have no right to stand for any programs they believe are important. He writes: “there is nothing inherently undemocratic about knowing more than a novice. Inappropriate use of self-direction only belittles the educator and confuses the learner". Fostering people's SDL does not equal to abandoning our principles and goals as educators, in a misguided act of pedagogic renunciation and populist demagogy. Self-direction can be more accurately viewed as part of a democratic tradition which holds that people's definitions of what is important to them should frame and instruct institutions’ or governments' actions, and not the other way round. This is why self-direction is usually seen as an abomination to advocates of national curricula, and why it is opposed by those who see education as a process of induction into cultural literacy (Brookfield, 1993). SDL entails trusting people/learners to make decisions.

An interesting model for SDL is that proposed by Brockett & Hiemstra (1991), and denominated as the Personal Responsibility Orientation (PRO) Model. An important element of this model is the notion of personal responsibility, which these 2 authors define as “individuals assuming ownership for their own thoughts and actions”. Only by accepting responsibility for one's own learning it is possible to take a proactive approach to the learning process. These assumptions are largely draw from humanism, including considering the learner independent, autonomous, and responsible to make decisions leading to self-actualization. In other words, we cannot be independent if we are not responsible and accountable for our choices, actions and consequences. As written by Brockett and Hiemstra (1991): “Self-direction is not a panacea for all problems associated with adult learning. However, if being able to assume greater control for one's destiny is a desirable goal of adult education (and we believe it is!), then a role for educators of adults is to help learners become increasingly able to assume personal responsibility for their own learning”. Another helpful self-directed learning instructional model is that proposed by Grow (1991, 1994), designated as Staged Self-Directed Learning (SSDL) model, which outlines how teachers can promote self-directed learning in their students (Merriam et al, 2007).

SDL also promotes and sustains learning how to learn, and life-long learning. Through SDL adults can gain new metacognitive skills about their learning efforts (Kasworm, 2011). In addition, the ability to learn on our own is absolutely critical, in a world that keeps changing and producing new information and knowledge every day. The findings of a large and meticulous study (Lyman, & Varian, 2003; as cited in Guglielmino, 2013), at the University of California, Berkeley, indicated that new stored information almost doubled between 1999 and 2002, growing at an estimated 30% per year. Google CEO Eric Schmidt made an announcement in 2010 that dwarfed its impact when he detailed the exponential escalation of the production of new information. Schmidt asserted, “Every two days we create as much information as we did from the dawn of civilization until 2003: five exabytes of data” (Kilpatrick, 2010, as cited in Guglielmino, 2013). In the past, education was seen as preparation for your entire life. In the late 1940’s, an individual could expect to graduate from high school with 75% of the knowledge needed to remain successfully employed until retirement. Fifty years later, that figure decreased to 2% (Barth, 1997). Just as childhood learning is no longer enough adequate preparation for life, initial training or learning is not an adequate preparation for maintaining competence on the job or in a profession. Therefore, in the present era of constant change and new information being added every day it is realistically not possible to have tutors that are constantly guiding us through our learning. SDL, therefore, becomes absolutely necessary as an instrument of development for individuals in the 21st century.

Finally, within the medical education field, the Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME) in the United States has endorsed SDL as a requirement of the medical school curriculum:

“Medical school faculty ensures the curriculum includes SDL experiences and independent study to allow students to develop lifelong learning skills. SDL involves students’ self-assessment of learning needs; independent identification, analysis, and synthesis of relevant information; and credibility appraisal of information sources” (www.lcme.org/publications/2015-16-functions-and-structure-with-appendix.pdf).

References

- Barth, R. (1997). The principal learner: A work in progress. Cambridge, MA: International Network of Principals’ Centers, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

- Brockett, R. G., & Hiemstra, R. (1991). Self-direction in adult learning: Perspectives on theory, research and practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Brookfield, S. (1986). Understanding and facilitating adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Brookfield, S. (1993). Self-directed learning, political clarity, and the critical practice of adult education. Adult Education Quarterly, 43: 227-242.

- Candy, P.C. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning: A comprehensive guide to theory and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Frambach, J.M., Driessen, E.W., Chan, L.C., & van der Vleuten, C.P. (2012). Rethinking the globalization of problem-based learning: How culture challenges self-directed learning. Medical Education, 46: 738-47.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Seabury Press.

- Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (20th anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Continuum.

- Grow, G. O. (1991). Teaching learners to be self-directed: A stage approach. Adult Education Quarterly, 41: 125-149.

- Grow, G. O. (1994). In defense of the staged self-directed learning model. Adult Education Quarterly, 44: 109-114.

- Grow, G. O. (1994). In defense of the staged self-directed learning model. Adult Education Quarterly, 44: 109-114.

- Guglielmino, L.M. (2013). The case for promoting self-directed learning in formal educational institutions. SA-Educ Journal, 10: 1-18.

- Hiemstra, R. (2013). Self-Directed Learning: Why do most instructors still do it wrong? International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 10: 23-34.

- Kasworm, C. (2011). New perspectives on post-formal cognitive development and self-directed learning. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 8: 18-28.

- Kilpatrick, M. (2010). Google CEO Eric Schmidt: “People aren't ready for the technology revolution.” ReadWriteWeb [http://readwrite.com/2010/08/04]

- Knowles, M. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. New York, NY: Association Press.

- Knowles, M., Holton, E., III, & Swanson, R. (1998). The adult learner (5th Ed.). Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing.

- Lyman, P., & Varian, H.R. (2003). How much information? [http://www2.sims.berkeley.edu/research/projects/how-much-info-2003/ execsum.htm ]

- Merriam, S. B. (2001). Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory (New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 89). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Merriam, S.B., Caffarella, R.S. & Baumgartner, L.M. (2007). Learning in adulthood: A comprehensive guide. (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Merriam, S.B., Caffarella, R.S. & Baumgartner, L.M. (2007). Learning in adulthood: A comprehensive guide. (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Poole, G. (2012). The culturally sculpted self in self-directed learning. Medical Education, 46: 735–73

- Rogers, C. R. (1983). Freedom to learn for the 80s. Columbus, OH: Merrill

Reviewed for May 2014 by

Gerardo E. Guiter, MD

Assistant Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine,

Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar,

Doha, Qatar.