Introduction

Simulation provides an innovative venue for supporting health care professional (HCP) discharge teaching, transferring the philosophical underpinnings of a learner-centered approach to the patient discharge teaching context. Designing health care professional curricula to include this approach for discharge teaching is critical to delivering family centered care and optimizing patient outcomes. This paper will provide a brief synopsis of the theory underpinning simulation as a learning modality for this population, the relevance for achieving a truly family centered care approach and a six-step approach to successfully designing this curriculum.

Background

Today in Health care professional curricula, learners are taught how to provide discharge teaching in their clinical practicums specific to the population/course of study. There is an expectation that all health care professional staff and learners deliver family/patient centered care.

In family/patient centered care the family/patient as the unit of care has the inherent strengths and abilities to improve their confidence and competence with health issues but must be afforded opportunities to practice and demonstrate competence.(1) To date the assumption that family centered care is achieved when health care professionals listen to families, hear their concerns, and support the concerns with information like discharge teaching has been considered sufficient. However inherent in this approach is an assumption that families will be able to apply the information as taught in non-emergent and emergent events outside of the tertiary care facility? Although simulation has gained popularity as a learning modality in health professional education there is a paucity of research examining this assumption and the benefit of using simulation in patient/family discharge teaching. From a theoretical perspective the feasibility and potential effectiveness of using simulation in this context is clearly supported by the theory underpinning family centered care and simulation as a learning modality. As such, simulation provides a new venue for optimizing both family/patient centered care and consequently family/patient outcomes and a new need for developing this focused curriculum in health care professional studies.

Theoretical Underpinnings

Simulation is supported by experiential learning theory and the theory of mastery learning. (2, 3) It is a modality that creates an opportunity for the learner, regardless of role designation, to acquire deliberate practice with coaching in a risk free environment. Experiential learning theory emphasizes the importance of providing a realistic experience with an opportunity for reflection, abstract conceptualization, and direct experimentation to facilitate learning and best practice.(2) In embracing this learning modality educators are given an objective window into the learner’s real needs as they directly observe learners applying knowledge/skill/attitude in the concrete experience. Educators provide the learner with feedback, which can vary in nature depending on the observation. For example often when the learner does something unexpected there is a need to understand the thoughts that drove the action to really unfreeze and support the assimilation or accommodation of new understanding/knowledge/skill. In contrast there are times when direct feedback is most appropriate and effective to provide the necessary knowledge/skill/attitude. In this case learners are given access to the knowledge and further opportunities to directly experiment and practice application of the knowledge/skill. Mastery learning is also underpinned by the theory that opportunities for deliberate practice with coaching will support learners in mastering the expectation; achieving the defined competence.(3) When we look at both theories and the assumptions underpinning family/patient centered care, we can see that providing opportunities for patients/families to demonstrate application of knowledge and skill is important to supporting confidence and competence. Learners don’t know what they don’t know and it often takes an opportunity to apply the knowledge/skill to discover a gap in knowledge/skill or gain awareness of inaccurate assumptions that may be guiding less than optimal behavioral responses.

In a recent study examining the benefit of simulation for supporting caregiver management of seizures, currently under review for peer publication, one of the caregivers when given the opportunity to manage a seizure on the manikin started to blow all over the child. This caregiver had received traditional discharge teaching by numerous health care professionals but in all of those sessions, the caregiver’s thoughts that fever was contributing to the child’s seizure was not realized or explored until this opportunity. By coaching this caregiver and inquiring into the thoughts that drove the need to blow on the child, we were able to support a new understanding of the lack of benefit cooling has in an emergent seizure of this nature. Lowering the child’s temperature was not going to stop the seizure, and it was more important to provide seizure management inclusive of timing the seizure, delivering the rescue medication after 5 minutes of seizure activity, and the provision of post seizure care. This caregiver reported being more confident and her simulation session on discharge teaching ended when we observed competent behaviors in all phases of seizure management.

The Use of Simulation

Simulation can be resource intensive and expensive and health care institutions and tertiary care centers are in need of evidence to support the use of this learning modality to sustain access and funding.(4, 5) Increasing the capacity of using this technology for discharge teaching creates a new venue for using simulation, as well as having a potential benefit for health care professionals. It also holds promise for improving confidence and competence in vulnerable patients and families leaving a tertiary care facility with instructions on how to manage another medical event should it reoccur. It is also a training tool for HCPs providing patient education to allow for additional experience and content evaluation. Expert modeling videos can also be developed using simulation to allow another medium of tools for parents to have available.

Curriculum Design

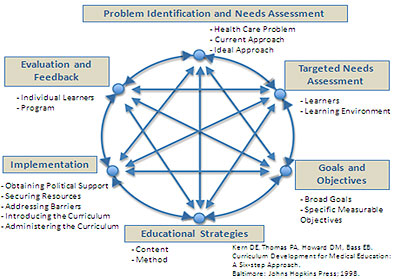

Kern’s six-step approach to curricula design supports both traditional and simulation based discharge teaching. (6) The problem is defined (Step1) and through hospitalization and conversations with families/patients a needs assessment is conducted to tailor information to meet family/patient needs (Step 2). This occurs in the same way for traditional/simulation based discharge teaching. Health care professionals need to understand more about the problem and the learners to provide effective teaching. However to optimize simulation, health care professionals need to pay close attention to the details shared by the patient/family so they can create appropriate learning objectives (Step 3) and content (Step 4 scenario) to enhance realism for curriculum implementation. With the seizure study, this involved asking the caregivers about the child’s seizures, when they occur, where they occur, what they look like and what caregivers they have been instructed to do. The delivery of the curriculum (Step 5) is where simulation provides an objective window into the learner’s real needs as learners are given an opportunity to demonstrate the application of knowledge/skill. The assessment (Step 6) is a repetitive process allowing the learner to demonstrate application of knowledge/skill with facilitated coaching until the learner verbalizes confidence and demonstrates competence.

Essential in this type of curriculum is a focus on how to deliver feedback and coach patients/families in deliberate practice to optimize learning. This is where learners need to really understand the theoretical underpinnings of experiential and mastery learning, and effective feedback to promote patient/family confidence and competence. Debriefing with good judgment developed by a group of educators at the center for medical simulation in Boston should be included in this part of the curriculum. (7) Most health care providers are already competent with giving direct feedback but are rarely equipped with a framework for authentic inquiry into the thoughts that drive actions. Debriefing with good judgment provides such a framework. Learners are taught to describe their observation, their concern, and develop a statement of authentic inquiry into an observed behavior to discover possible false assumptions or understandings that may be impeding appropriate management. Unexpected behaviors should be a flag to using this approach and framework. Again critical to success is the provision of opportunities for the learners to practice till they can verbalize confidence and demonstrate competence.

Conclusion

Patient and Family education is key in the continuum of care. To provide a higher level of evaluation, health care professionals should be encouraged to follow up with families/patients to ascertain the sustainable effects of deliberate practice. Debriefing is an essential element in this process. In addition health care tertiary care facilities should consider developing a training facility or room to provide families and patients access to deliberate practice with coaching. The development of Just-in-Time Simulation room for families is a new concept but a worthy concept if we are to raise our confidence and competence in the provision of truly family/patient centered care.

References

- Dunst C, Trivette C, Deal A. Supporting and Strengthening Families Vol. I: Methods, Strategies and Practices. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books.; 1994.

- Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc; 1984.

- Bloom B. Time and learning. American Psychologist. 1974:682-8.

- Issenberg BS, Mcgaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review*. Medical Teacher. 2005;27(1):10-28.

- McGaghie W, Issenberg S, Petrusa E, RJ S. A critical review of simulation-based medical education research 2003-2009. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):50-63.

- Kern DE, Thomas PA, Howard DM, Bass EB. Curriculum Development for Medical Education. Baltimore, Maryland, USA: John Hopkina University Press; 1998.

- Rudolph J, Simon R, Rivard P, Dufresne R, Raemer D. Debriefing with Good Judgment: Combining Rigorous Feedback with Genuine Inquiry. Anesthesiology Clin. 2007;25 361–76.

Reviewed for June 2014 by

Elaine Sigalet, PhD

Director, Development and Continuing Education

And

Joanne Davies Msc/Edu

Director, Simulation Center and Services

Sidra Medical and Research Center,

Doha, Qatar.